My recent experience with writing APIs in Go has forced me to confront something that many seasoned developers would consider obvious: Writing tests and writing testable code are two very different challenges. Specifically, I have struggled to write tests involving HTTP interfaces.

Approaches to testing that seemed obvious in the context of countless examples consistently seemed alien when applied to my own code. Then it struck me, the examples I’d been reading were focussed on demonstrating how to write tests and not how to write testable code.

In this post, I start with a project that represents the APIs I have been building and use it as an example to explore how to write testable HTTP interfaces in Go.

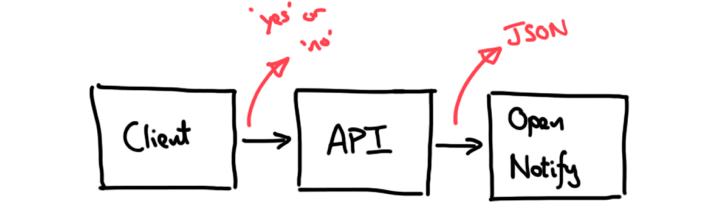

The API: Is Anyone Out There?

To learn how to write testable code, I’m going to build an API that tells me if anyone is currently in space. These hastily written user stories provide a little more detail.

- I’d like to know whether there is anyone in space right now.

- I’d like to be given a simple answer, “yes” or “no”.

- I’d like my answer to be provided in response to an HTTP request.

Open Notify provides an API that will help us answer the question of whether anyone is in currently in space, but it fails to meet our simplicity requirement. A sample response from this API can be seen below.

{

"number": 2,

"people": [

{

"craft": "ISS",

"name": "Joe Acaba"

}, {

"craft": "ISS",

"name": "Anton Shkaplerov"

}

],

"message": "success"

}

We can use this information to answer our question, but we need to wrap this response with our own code in order to meet our requirement for simplicity. We need our answers to be transformed to the more succinct, “yes” or “no”. The code snippet below shows what we are aiming for.

$ curl -i http:/localhost:8000/anyonethere

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Fri, 16 Feb 2018 08:29:07 GMT

Content-Length: 3

Content-Type: text/plain; charset=utf-8

yes

We’ll build this API in two parts:

- a client for the Open Notify API

- a server that uses our client to query the number of people in space and return a simplified answer

We’ll explore testing each of these in isolation before combining them to look at testing the completed API. As this post focusses on writing testable code, I’m going to make the assumption that you are familiar with the basics of making HTTP requests and serving HTTP responses in Go.

The Client

Our client is relatively simple. It queries the Open Notify API and parses the result into a struct for use in our Go code. Responses will be marshalled into the structs shown below.

// PeopleInSpace represents the number of people in space. It includes

// their names and the name of their space craft.

type PeopleInSpace struct {

Number int `json:"number"`

People []Person `json:"people"`

Message string `json:"message"`

}

// Person represents details about an individual in space.

type Person struct {

Craft string `json:"craft"`

Name string `json:"name"`

}

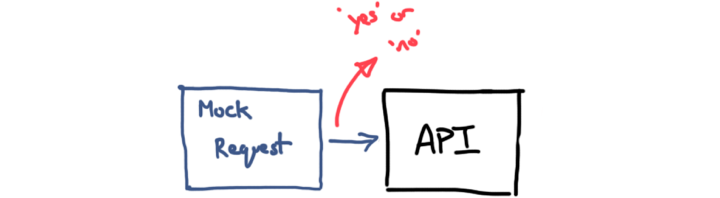

When considering tests for the HTTP client, I wanted to decouple myself from the real Open Notify API. I wanted the ability to test offline and I wanted complete control over the data I used in testing. This latter requirement is something that becomes increasingly important when testing failure conditions.

Go’s httptest package provides a local server we can use during testing to mock external responses. To use this for testing, we must configure our client such that it sends requests to this test server rather than the real Open Notify API.

- Rule #1: Ensure that all external URLs are configurable properties that can be set at runtime.

Creating a client struct that holds configuration values enables us to configure the client to use a local httptest server during testing. Although not strictly necessary, we provide a helper function to create a Client configured with the default URL.

type Client struct {

BaseURL string

}

func NewClient() *Client {

c := &Client{

BaseURL: "http://api.open-notify.org",

}

return c

}

Our test code can now focus on configuring the mock server and executing tests against it.

- Create a function that returns our mock response.

- Create a mock server and have it reply to requests with our mock response.

- Create an instance of our client.

- Configure the client to use the URL of our mock server instead of the real API.

- Call methods on the client and test the results.

These five steps outline how we use our client in testing but we will explore each of these in more detail below.

First, we need to create a function that returns a response that matches what we would expect from our external service. We could take this from the documentation, but I’d strongly recommend using a sample response from the real API.

func sampleGet(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

fmt.Fprint(w, `

{

"number": 4,

"people": [

{"craft": "ISS","name": "Alexander Misurkin"},

{"craft": "ISS","name": "Mark Vande Hei"},

{"craft": "ISS","name": "Joe Acaba"},

{"craft": "ISS","name": "Anton Shkaplerov"}

],

"message": "success"

}`)

}

Next, we need to create an instance of our mock server and configure it to call our mock function, sampleGet.

func testServer() *httptest.Server {

return httptest.NewServer(http.HandlerFunc(sampleGet))

}

Our mock server is now ready for testing. We create an instance of our client and configure it with the URL of our mock server. Our client can now be used as if it were pointing to a real endpoint. The example below shows a simple test but is by no means comprehensive in its test coverage.

func TestGetPeopleInSpace(t *testing.T) {

server := testServer()

defer server.Close()

tc := Client{

BaseURL: server.URL,

}

t.Log("Given the need to test the PeopleInSpace API client.")

t.Logf("\tWhen making a request to \"%s\"", tc.BaseURL)

pis, _ := tc.GetPeopleInSpace()

t.Logf("\tWhen querying the number of people in space")

if pis.Number != 4 {

t.Error("\t\tshould return 4.", pis.Number, cross)

}

t.Log("\t\tshould return 4.", tick)

}

The complete code for testing our client is available here: billglover/learn-httptest/client

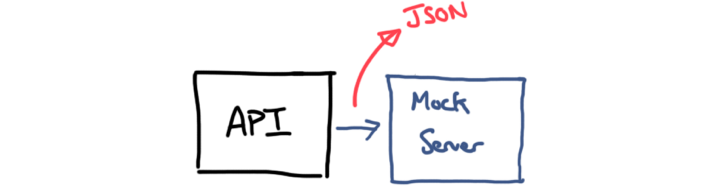

The Server

Our API server responds inbound requests by returning a simple, “yes” or “no” to indicate whether there is anyone in space.

When testing server code, I have struggled to figure out how to access responses to HTTP requests without running an instance of the server. We can avoid the need to run the server by creating a mock Request and passing it directly to the ServeHTTP. I was struggling with this because the way I had been structuring my code didn’t expose the route handlers. One way to do this is to create a function that registers your route handlers and then call it during test set-up.

- Rule #2: Separate out route definitions so that they can be called from your tests.

Note, in the example below I have chosen to do this by returning a new ServeMux, but you could simplify this still further if you opt to use the DefaultServeMux instead.

func routes() *http.ServeMux {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.HandleFunc("/anyonethere", anyoneThereHandler)

return mux

}

func anyoneThereHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

fmt.Fprintln(w, "no")

}

Once you have a mechanism for defining your routes, testing is relatively straightforward.

- Configure your routes using your server code.

- Create your

Requestas if it had arrived externally. - Create a

ResponseRecorderto capture the response. - Call

ServeHTTPon yourHandlerpassing yourResponseRecorderand yourRequest. - Use the values captured in the

ResponseRecorderto complete your tests.

We will walk through each of these steps in more detail.

Start by registering the route handlers during test set-up. This returns a ServeMux which will handle all requests using our servers route handlers.

mux := routes()

Create a test Request. At a minimum, this needs a path and a method. In our case, the API doesn’t require a request body, so we set this to nil.

r, err := http.NewRequest(http.MethodGet, "/anyonethere", nil)

if err != nil {

t.Fatal("\t\tshould be able to create request without error.", err, cross)

}

t.Log("\t\tshould be able to create request without error.", tick)

Now that we have our request, we pass it to our server by calling the ServeHTTP method directly on our route handler. The ServeHTTP method requires a ResponseWriter in addition to our Request. Go’s httptest package includes a ResponseRecorder that captures the response from our server and allows us to use it during test evaluation.

w := httptest.NewRecorder()

mux.ServeHTTP(w, r)

The ResponseRecorder gives us access to the fields from the response. In this example, we test that we received an HTTP 200 response code.

if w.Code != tc.code {

t.Error("\t\tshould return an HTTP 200 response.", w.Code, cross)

}

t.Log("\t\tshould return an HTTP 200 response.", tick)

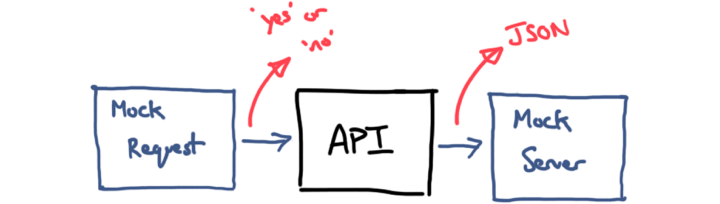

The Combination

Now that we have successfully tested making HTTP requests with our client and tested handling HTTP requests with our server, we need to combine these into a functioning API.

Combining the client and server introduces another challenge in that the client request is made during the handling of an inbound HTTP request. The function signature for our Handler function does not allow us to pass in a reference to the Client struct.

func anyoneThereHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {}

We need to modify the function signature to allow us to provide a reference to the Client when calling our route handler. The solution is to create a new function that doesn’t handle the Request directly, but itself returns an http.Handler that handles the request. This may seem complicated at first, but take some time to work through what is going on here.

The code below shows a modified anyoneThereHandler function that takes a pointer to the Client and returns a Handler function.

func anyoneThereHandler(c *client.Client) http.Handler {

return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

pis, err := c.GetPeopleInSpace()

if err != nil {

log.Printf("failed to query dependency: %v\n", err)

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

if pis.Number <= 0 {

fmt.Fprint(w, "no")

return

}

fmt.Fprint(w, "yes")

})

}

With our handler now able to use our Client, we modify our routes() function to provide a pointer to the Client.

func routes(c *client.Client) *http.ServeMux {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.Handle("/anyonethere", anyoneThereHandler(c))

return mux

}

Now that the server can access the Client from within the Handler function, we have all the pieces in place to combine the approaches for testing both the client and the server. We have built ourselves a testable API.

// Create our mock handler (assume tc.code and tc.json mock the desired responses

// from the Open Notify service.

handler := func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.WriteHeader(tc.code)

fmt.Fprint(w, tc.json)

}

// Create an instance of our test server and pass it our handler. This server

// will mock the Open Notify service.

server := testServer(handler)

defer server.Close()

// Configure our client to use our mock server.

client := &client.Client{

BaseURL: server.URL,

}

// Create our route handler and pass in our client.

mux := routes(client)

// Create a request for our api.

r, _ := http.NewRequest(http.MethodGet, "/anyonethere", nil)

// Create an instance of the RepsonseRecorder pass it to the ServeHTTP function

// on our route handler.

w := httptest.NewRecorder()

mux.ServeHTTP(w, r)

// We can now test the Response.

if w.Code != tc.code {

t.Error("\t\tshould return an HTTP 200 response.", w.Code, cross)

}

t.Log("\t\tshould return an HTTP 200 response.", tick)

The code for working examples of our client, server and full API are available on GitHub

--- PASS: TestTable (0.00s)

main_test.go:46: Given the need to test the PeopleInSpace API server against a mock service.

main_test.go:50: When making a request against a mock indicating: one person in space

main_test.go:70: should be able to create request without error. ✓

main_test.go:79: should return an HTTP 200 response. ✓

main_test.go:85: should be able to decode response without error. ✓

main_test.go:90: should return yes. ✓

main_test.go:50: When making a request against a mock indicating: no one in space

main_test.go:70: should be able to create request without error. ✓

main_test.go:79: should return an HTTP 200 response. ✓

main_test.go:85: should be able to decode response without error. ✓

main_test.go:90: should return yes. ✓

main_test.go:50: When making a request against a mock indicating: a dependency failure

main_test.go:70: should be able to create request without error. ✓

main_test.go:79: should return an HTTP 200 response. ✓

main_test.go:85: should be able to decode response without error. ✓

main_test.go:90: should return . ✓

PASS

ok github.com/billglover/learn-httptest/api 0.022s

Footnote: Handler vs. HandlerFunc

To fully understand testing HTTP calls in Go, I first had to understand the HandlerFunc. If you’ve read a Go book or followed any Go tutorials online, you’ll have come across the HandlerFunc. Understanding how this type helps us when serving HTTP requests has proved invaluable.

The definition of the HandlerFunc type is short.

// The HandlerFunc type is an adapter to allow the use of

// ordinary functions as HTTP handlers. If f is a function

// with the appropriate signature, HandlerFunc(f) is a

// Handler that calls f.

type HandlerFunc func(ResponseWriter, *Request)

// ServeHTTP calls f(w, r).

func (f HandlerFunc) ServeHTTP(w ResponseWriter, r *Request) {

f(w, r)

}

But we also have http.Handler.

// A Handler responds to an HTTP request.

type Handler interface {

ServeHTTP(ResponseWriter, *Request)

}

So what is the difference between them?

// Handle registers the handler for the given pattern

// in the DefaultServeMux.

// The documentation for ServeMux explains how patterns are matched.

func Handle(pattern string, handler Handler) {

DefaultServeMux.Handle(pattern, handler)

}

// HandleFunc registers the handler function for the given pattern

// in the DefaultServeMux.

// The documentation for ServeMux explains how patterns are matched.

func HandleFunc(pattern string, handler func(ResponseWriter, *Request)) {

DefaultServeMux.HandleFunc(pattern, handler)

}

Following these definitions through http package in the standard library, we also find the ServeMux. This shows us the following.

// Handle registers the handler for the given pattern.

// If a handler already exists for pattern, Handle panics.

func (mux *ServeMux) Handle(pattern string, handler Handler) {

// ...

}

// HandleFunc registers the handler function for the given pattern.

func (mux *ServeMux) HandleFunc(pattern string, handler func(ResponseWriter, *Request)) {

mux.Handle(pattern, HandlerFunc(handler))

}

And there we have it, the HandlerFunc is a type that implements the Handler interface. It is as simple as that.