I’ve decided to start reading more technical papers. First up, is the paper that introduces Oblivious DNS, a privacy centric alternative to DNS. These are my notes.

The Domain Name System (DNS) works wonders for the modern internet. Created in 1983 by Paul Mockapetris, DNS provided a scalable way to map names to addresses on the ARPANET. When DNS works well we take it for granted. Yet there are scenarios when threats to the integrity of DNS can cause havoc.

I once worked at an organisation where 53% of DNS queries failed to return any results at all. That figure looked even worse when you accounted for queries returning invalid results. The solution was to a hopeless exercise to sync hosts files across the data centre by hand.

This example is frustrating but somewhat comical. But it is possible to exploit the DNS system in more nefarious ways. One of the techniques used to control access to the information is DNS poisoning. By swallowing DNS requests or poisoning the results it is possible to block access to resources on the internet. These attacks are crude and coarse grained. By targeting DNS, they disrupt access to domains rather than specific content.

When used to block content, the results are frustrating but usually obvious to the user. There is a far less visible threat posed by the current design of DNS, a threat to user privacy.

I’ve run a PiHole at home for a couple of years. For those who haven’t come across it, PiHole is a network wide ad-blocker. You configure all your devices to use the PiHole instead of your default DNS provider. It exploits the DNS system to block advertising and tracking.

The PiHole also gives you optional DNS statistics. These statistics tell a worrying story. Anyone who has access to my DNS queries is sat on an information goldmine.

- You can see which Smart Home devices we have

- You get a comprehensive overview of the services we use

- You can determine patterns of behaviour

- You can make a good guess at my employer

- You have a list of all sites I visit and the time I visited them

The reality though is that for many of us, someone does have access to this information. Our ISPs provide a default DNS service and many of us never change this. When switch providers, we are handing this information to someone else instead.

With this understanding, the announcement of Oblivious DNS over HTTPS (ODoH) by a team from the University of Washington and Cloudflare caught my attention. Intrigued, I decided to read the original Oblivious DNS (ODNS) paper.

Oblivious DNS: Practical Privacy for DNS Queries

Authors:

- Paul Schmitt

- Anne Edmundson

- Allison Mankin

- Nick Feamster

Published: Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies

Source: https://odns.cs.princeton.edu/pdf/pets.pdf

Date: 2019-04-01

Reference: 10.2478/popets-2019-0028

The Challenge?

The starting point for much of our activity online is a DNS query. These DNS queries match domain names (e.g. billglover.me) with their corresponding IP address (e.g. 64.227.35.88).

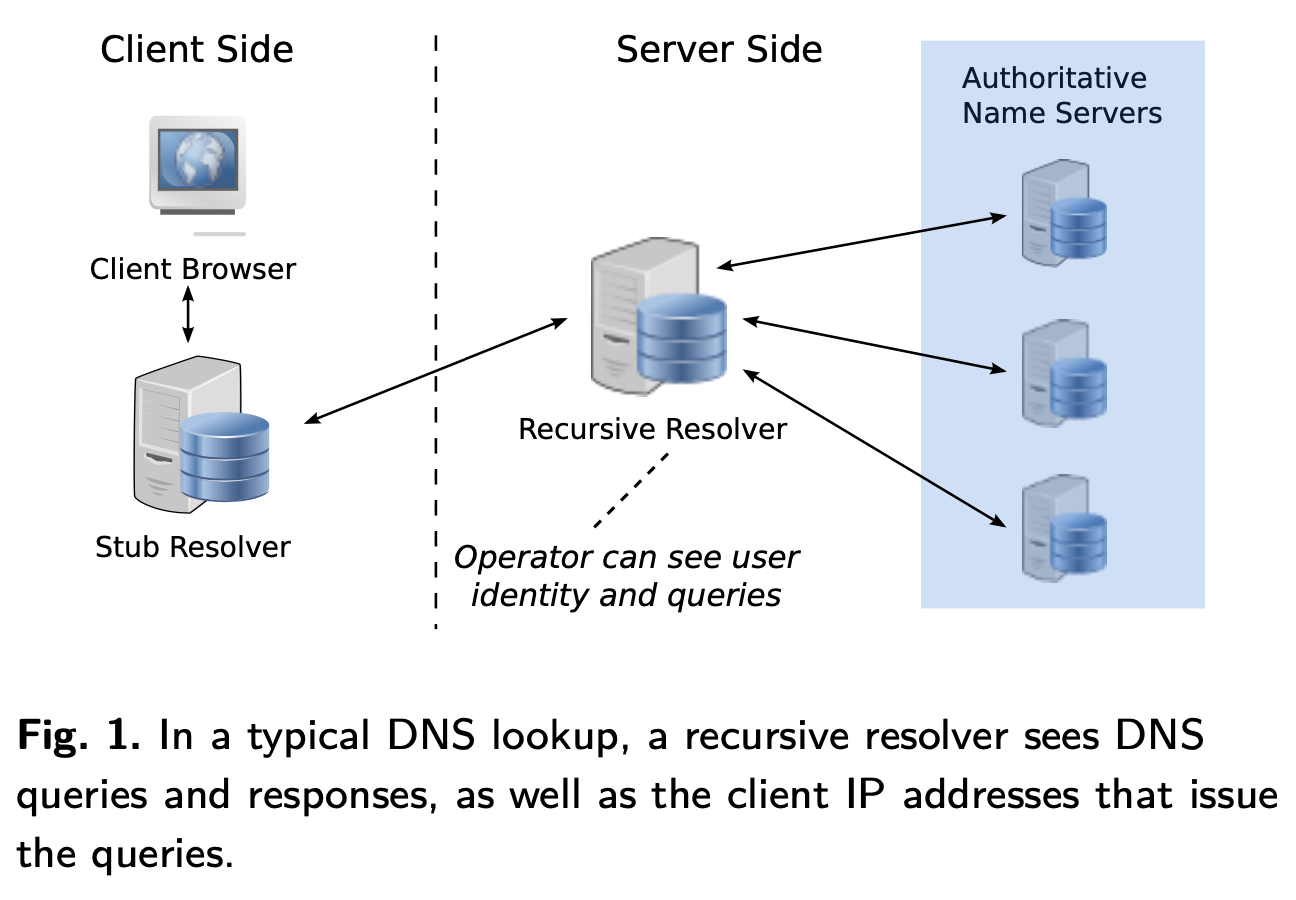

DNS is a hierarchical system. The first stop for a DNS query is the recursive resolver. The recursive resolver attempts to answer the query based on cached information. If it doesn’t know the answer it queries the DNS hierarchy on behalf of the client.

For most of us, our Internet Service Provider (ISP) provides a recursive resolver. Configuration is automatic, and the majority of users leave this unchanged. This presents a privacy challenge.

“Recursive DNS resolver operators can readily associate and track client identities (i.e., IP addresses) along with information about their DNS queries, creating a fundamental point of privacy risk.”

Your ISP knows who you are. They also have a single point to collect every DNS query made by devices on your network. Think of it as a log:

2021-01-01 06:30 Bill meethue.com

2021-01-01 07:00 Bill stream.sonos.com

2021-01-01 07:01 Bill me.apple.com

2021-01-01 07:06 Bill ft.com

2021-01-01 07:15 Bill gmail.com

...

2021-01-01 09:27 Bill vpn.employer.com

...

2021-01-01 16:30 Bill netflix.com

...

I’ve simplified this to make a point. In reality the log is noisier and filled with tens of thousands of requests.

“DNS traffic can reveal personal information about users’ browsing behavior as well as the types of devices in a network. The vantage point provided at the recursive DNS resolver gives the operator of the resolver visibility into the IP addresses that query various domain names, which may be ultimately linked to individual devices, sets of devices, or user identity.”

If the operator of a recursive resolver has access to this information, it doesn’t mean they are going to use it. But, in the age of hyper-accurate behaviour profiling, there are strong incentives to do so.

There are options for encrypting DNS traffic. These prevent a third party from reading messages sent between client and recursive resolver. There are are approaches that add authentication to the mix. These do not prevent the operator of a recursive resolver seeing both user identity (IP address) and the contents of DNS queries.

For users who don’t trust their ISP, one common mitigation is to switch to a different DNS provider. This isn’t a solution as much as a mitigant. It shifts the point of trust, but leaves the single point of privacy exposure.

Oblivious DNS attempts to solve this.

How it works?

Oblivious DNS takes a different approach to DNS privacy. By decuopling the client identiy from the DNS query, ODNS mitigates the privacy threat outlined above.

“If the recursive resolver is unable to know the DNS queries that a client has issued, the DNS operator is unable to provide an adversary with the requested data and it will be able to remain oblivious to the requests and responses it serves.”

But making changes to a protocol like DNS isn’t without its challenges. The patchwork of organisations, software and hardware that keeps the internet alive doesn’t have an easy upgrade path. There isn’t a single point where we can apply a patch and fix vulnerabilities. Any new standards or technologies need to co-exist with existing deployments.

“ODNS decouples client identity from queries by leveraging the behavior of the global DNS system itself.”

But you can’t rely on existing infrastructure to follow documented standards. You need to leverage existing behaviour to work for you rather than against you. The internet is an example of Hyrum’s Law in full effect.

“ODNS operates in the context of the existing DNS protocol, allowing the existing deployed infrastructure to remain unchanged.”

Source: Oblivious DNS: Practical Privacy for DNS Queries, Figure 1

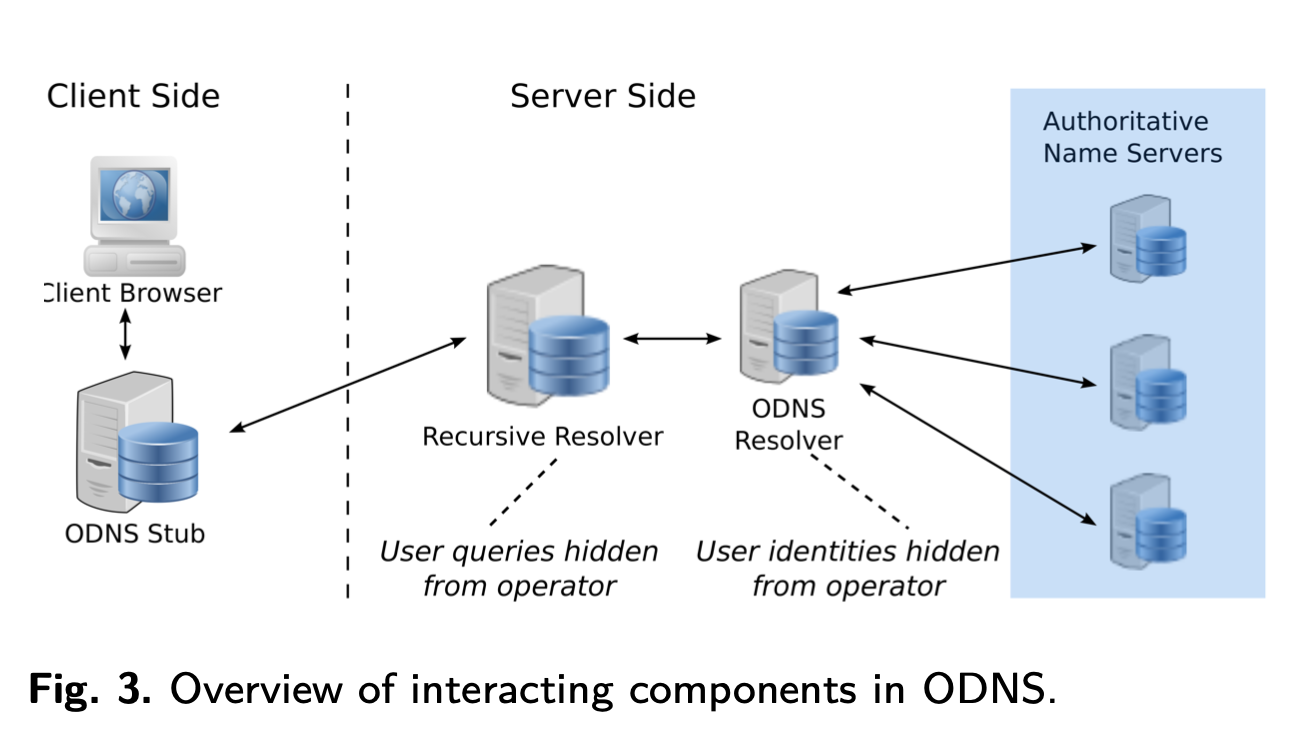

Oblivious DNS introduces two new components to the DNS architecture:

- A new ODNS stub resolver

- An ODNS resolver

Source: Oblivious DNS: Practical Privacy for DNS Queries, Figure 3

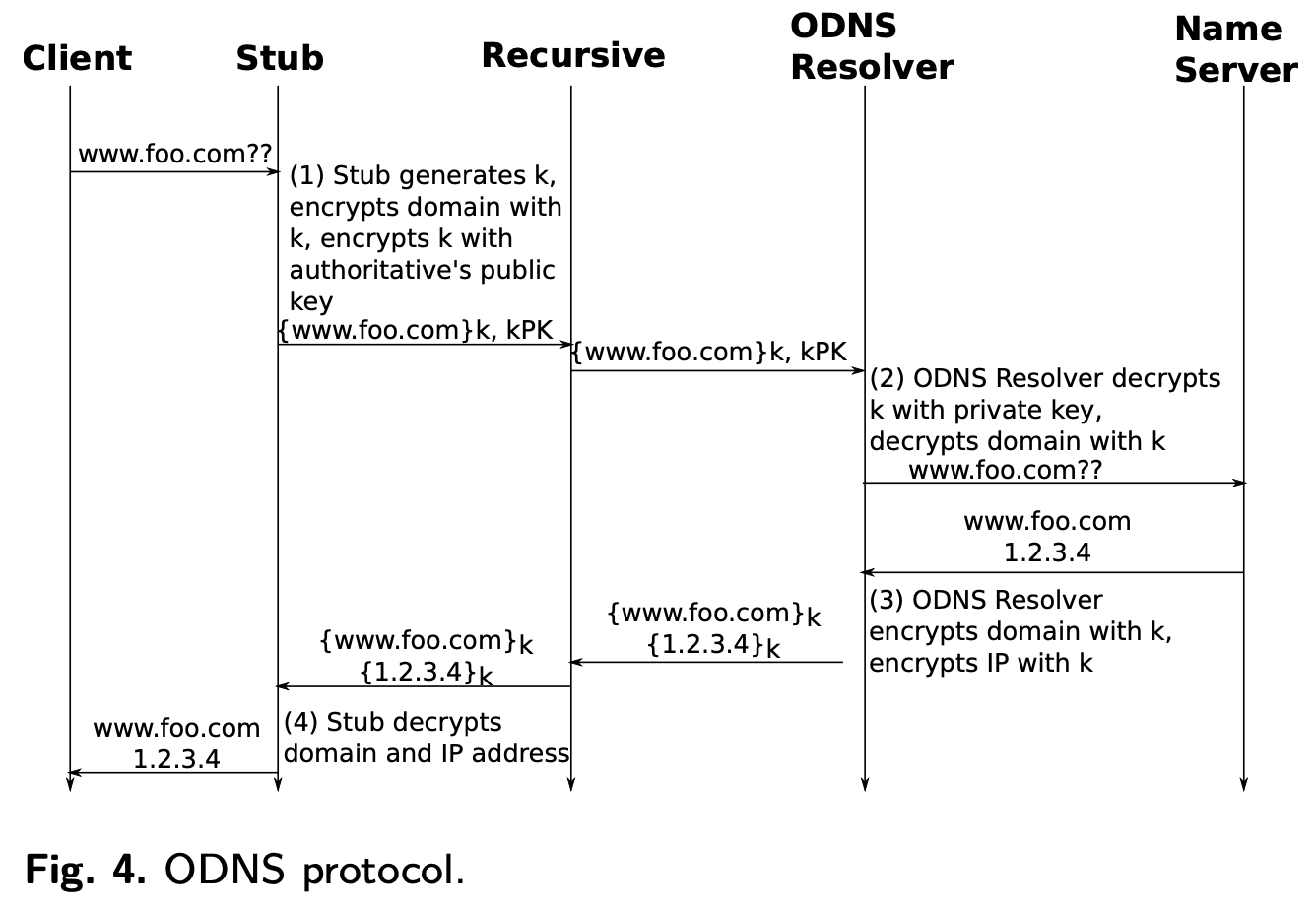

The OSNS stub generates a session key and uses it to encrypt client DNS queries. It then encrypts the session key with the public key of the ODNS resolver.

This encrypted request is then used to form a new DNS query. This query is passed on to the Recursive Resolver as before.

Give me the IP for:

example.com

Becomes:

Give me the IP for:

lfkashdfalssfdfasdfasasdfashmlasjlj.odns.com

The ODNS resolver receives this query and decrypts the session key. It then uses that session key to decrypt the original client request. Acting as a recursive resolver, it answers the client query and encrypts the response.

Source: Oblivious DNS: Practical Privacy for DNS Queries, Figure 4

The recursive resolver receives the client identity and an encrypted version of the DNS query. Because it doesn’t have access to the private key of the ODNS resolver, it is unable to decrypt request. The request looks like a normal DNS request, albeit for a seemingly random domain name.

The ODNS resolver doesn’t see the client identity. It sees the IP address of the recursive resolver. With access to the private key, it decrypts the original request. It is unable to associate this request with a user identity.

ODNS is a beautiful solution in its simplicity but it doesn’t cover all eventualities. The paper outlines the threat modeling and the goals in more detail.

“Our threat model includes any single non-colluding passive adversary who wishes to compromise the confidentiality of a client’s IP and requested domain name.”

Importantly, the paper outlines threats that aren’t addressed by ODNS. A global passive adversary or an active threat are both not considered. If you are trying to hide your query history from a nation state, you may find they have ways to get what they need.

The paper leaves open to future work, the combination of privacy enhancing technologies such as ODNS over HTTPS.

Challenges

The practical roll-out of ODNS presents a number of challenges. The paper explores these in some depth.

EDNS0

There are optimisations that can be made when DNS nameservers have access to information about the client. This gave rise to the EDNS0 client subnet option. This additional information allows DNS servers to return location specific IP addresses.

“the EDNS0 client subnet option allows upstream authoritative nameservers to learn the IP subnet of clients issuing queries. To achieve the intended privacy bene- fits of ODNS, the client subnet option should not be used.”

This stands out as an area of weakness for me. Although mitigation is discussed there isn’t much that can be done if recursive resolvers decide to pass on details of the client subnet. ODNS resolvers could identify where client information is being supplied and flag this to the client, or if necessary block these requests. It’s not clear to me what the right behaviour should be.

Scalability

“The ODNS resolver performs the role of both a typical authoritative server and a recursive resolver. Thus, the ODNS resolver may face higher traffic volume than a traditional authoritative nameserver. Additionally, the ODNS resolver is responsible for, and must expect, queries for pseudorandom hostnames within its zone. Thus, the ODNS resolver may be susceptible to DDoS attacks as it must attempt to decrypt all queries that it receives. We must thus design ODNS to handle the possibly high query volumes.”

Replication, or scaling out, is one possible solution. Operators can create multiple instances of the ODNS resolver to increase capacity. A global anycast address is assigned to each replica and advertised as the NS record for the ODNS server.

“When a recursive resolver sends a DNS query to the ODNS resolver, the query will be routed by BGP to a server that is nearby (according to wide-area routing).”

Key Distribution

This approach to scalability produces a challenge for key distribution. Sharing a private key across all replicas is risk. If one replica gets compromised it would compromise all replicas.

If each ODNS Resolver has a unique public key, we need a mechanism for key distribution to clients. Clients don’t know until request time which ODNS resolver will handle their request. One approach would be for clients to ask their closes ODNS resolver for its public key. The challenge with this is that doing so would expose the client identity to the ODNS resolver. This is something we want to avoid.

“Likewise, to preserve user privacy the key distribution must be done in a way such that the ODNS resolver never learns the identity (i.e., IP address) of a client. This disqualifies out-of-band key exchange”

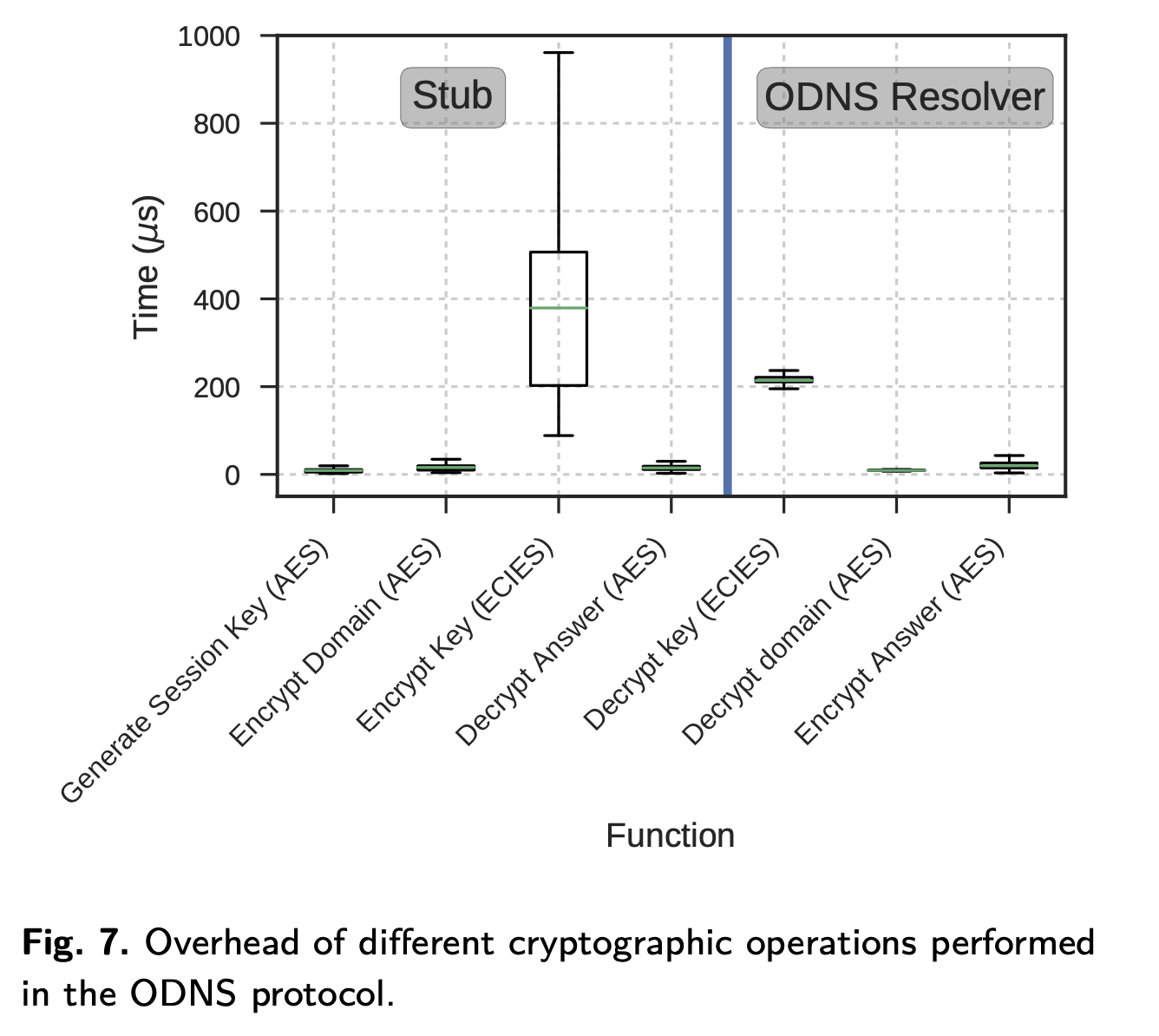

Source: Oblivious DNS: Practical Privacy for DNS Queries, Figure 7

ODNS solves this by having the client look-up the address and public key of its closest ODNS resolver using a special DNS query.

“The client’s stub re- solver sends a special ODNS query to the recursive resolver, which will in turn use the anycast address to locate the nearest ODNS resolver. The ODNS resolver that receives the query responds with an OPT record that includes a self-certifying name, such that the name of the server is derived from the public key itself and is associated with an instance of the ODNS resolver listening on the unique unicast IP address, and the ODNS resolver’s public key.”

This solution is my favourite part of the paper. Bouncing from anycast to unicast addressing whilst providing the public key in the DNS query response is inspired.

Performance

The design of ODNS means it is reasonable to expect to pay a small performance penalty in return.

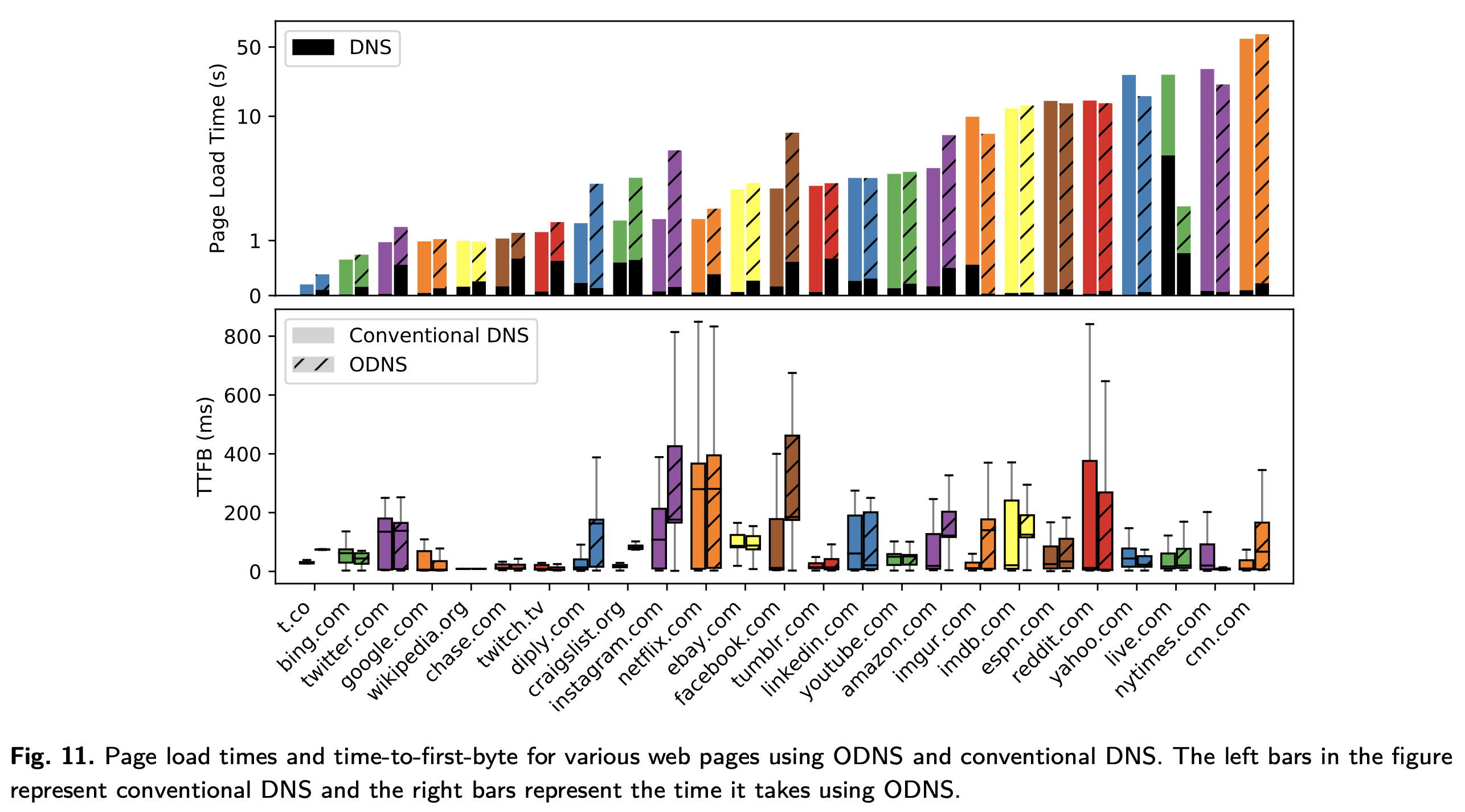

The extra latency at the client is due to the asymmetric encryption of the session key. But ODNS introduces some extra network hops to the ODNS resolver. The impact of this becomes evident when we look at page load times.

Source: Oblivious DNS: Practical Privacy for DNS Queries, Figure 11

“We measure how ODNS would affect a typical Internet user’s browsing experi- ence by evaluating the overhead of a full page load; a full page load consists of not only conducting a DNS lookup for the page, but also fetching the page, and conducting any subsequent DNS lookups for embedded objects and resources in the page.”

“We see that there is generally not a significant difference in page load time between ODNS and conventional DNS because DNS lookups contribute relatively little time to the entire page load process.”

Of more significance to page performance is the Time To First Byte (TTFB). The importance of TTFB has driven significant industry investment in Content Distribution Networks (CDNs). CDNs aim to serve data from as close to the user location as possible.

DNS servers can are often configured to return the IP address of a server closest to the user location. But by adding an ODNS resolver we remove the ability to determine user location. Authoritative servers will return IP addresses based on the location of the ODNS resolver and not that of the user.

“These results help explain the page load times we witness for several sites. For example, reddit.com and nytimes.com both achieve lower TTFBs using ODNS, indicating that they were directed to content servers that are closer than those resolved with conventional DNS. Accordingly, the ODNS page load times for those sites were faster when using ODNS. Likewise, when ODNS results in higher TTFBs such as with instagram.com, we see longer page load times.”

The solution is to ensure ODNS is deployed as widely as possible, although roll-out on a scale to rival current CDN deployments poses a real challenge.

“This insight motivates widespread deployment of ODNS resolvers and the use of anycast.”

I suspect there is more nuance to this and in many cases would trade a small performance hit for an increase in privacy.

Where Next

The paper concludes with a reminder that ODNS doesn’t mitigate all threats to the integrity of the DNS queries. Active threats or collusion between the operators of DNS and ODNS resolvers continue to leave users exposed.

Recommendations for future work focus on three key areas; deployment in the wild, standardisation, and further research.

“Various DNS standards and enhancements have improved the security and privacy of DNS, including DNSSEC, DNS-over-TLS (DoT), and DNS-over- HTTPS (DoH). ODNS is compatible with all of these enhancements, and it provides complementary privacy guarantees.”

Active research continues and the team recently published: Oblivious DNS over HTTPS (ODoH): A Practical Privacy Enhancement to DNS.

If you have any recomendations for papers I should read, I’d love to hear from you.