We are in the process of introducing a single daily bottle of milk formula to our son’s diet. It’s been five years since we last did this, and all memories of how to approach this, or how it went have long since faded.

This blog post isn’t about the reasons for introducing formula or the approach we’ve taken. This is about how people make mistakes and our ability to dismiss these mistakes as simple human error.

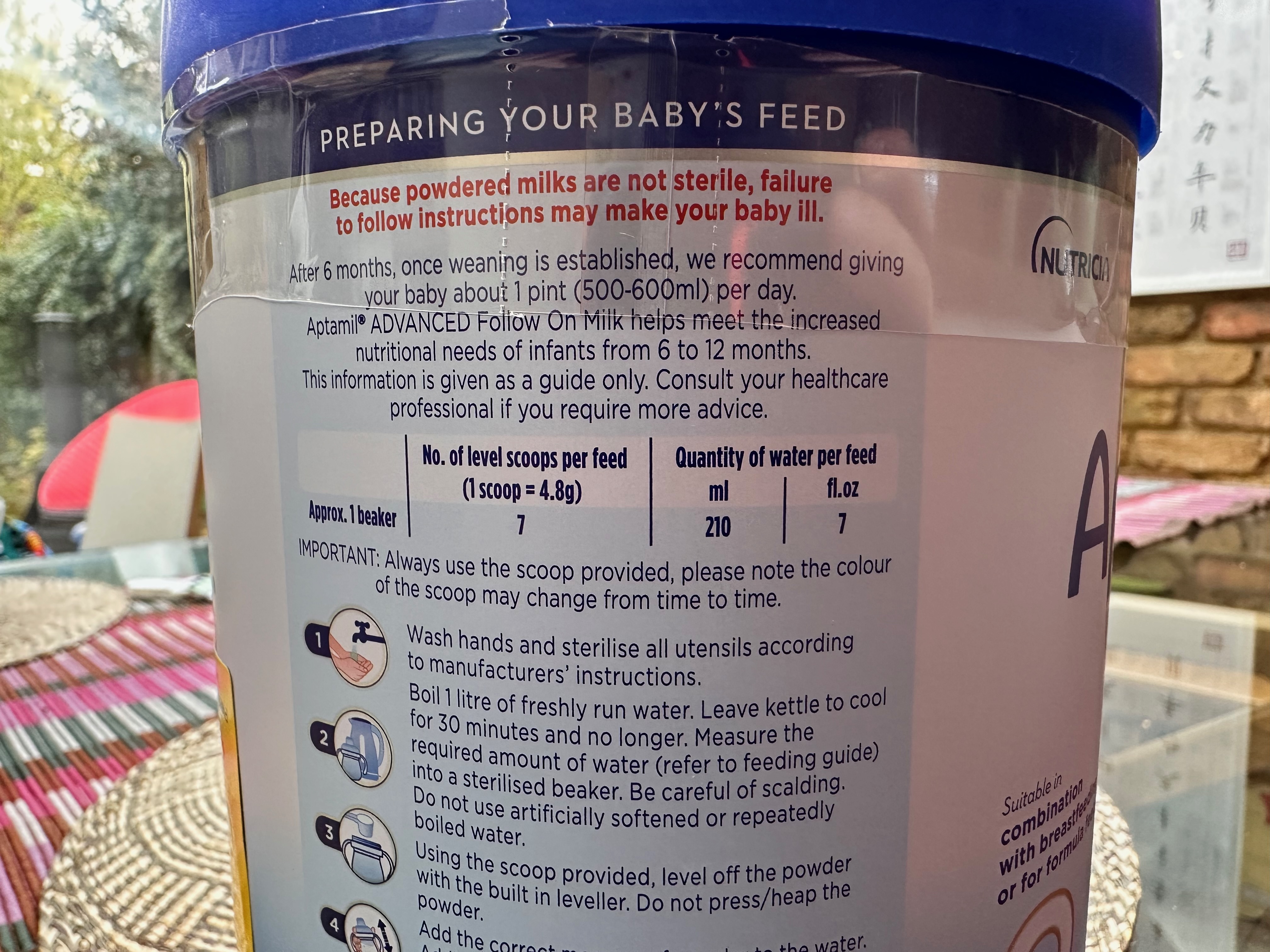

Photograph showing the instructions on the side of formula tub.

The Mistake

Detailed instructions for how to make up formula are printed on the side of the packaging. I read these through and would summarise the process as follows.

- Wash bottle

- Sterilise bottle

- Boil water

- Allow to cool

- Make formula

- Feed

The question I have for you is this:

“How many scoops of formula do I need in one beaker?”

This isn’t a trick question. I was using the quantity of water recommended for a single feed, 210ml. If you answered, 7, then you’d be correct, congratulations.

For some reason, I didn’t answer 7. I followed these instructions and instead added 1 level scoop of formula into the beaker. Oblivious to my mistake I proceeded to feed our son. It did not go well. He refused to take the milk, pulling his head back at each attempt, spitting it out if I ever managed to get him to take a mouthful.

So, I tried again the next day. I re-read the instructions and repeated the process with the same results. Our son isn’t, yet, a fussy eater. He will devour everything we put in front of him, so for him to refuse milk was unexpected.

Initially we thought this might have been a reaction to me feeding him. He’s not used to milk from Dad. So, we decided to let mum try. Unfortunately, the same results. He refused to take the milk. We tried again but with a different bottle. The same result.

Realisation

I can’t remember what prompted me to re-visit the instructions, but I picked up the tub of formula and noticed my mistake, I should have been using 7 scoops and not 1 scoop per bottle. I made a fresh bottle and tried again. This time, success. My son drank half a bottle and has progressively increased the amount he drinks with each subsequent feed.

Knowing what I’d done wrong, I asked my wife how many scoops she’d put in the bottle when she tried.

“One… that’s what it says on the side of the tub.”

And so I showed her the tub. We had both made the same mistake. But why?

The Cause

On discovering my mistake, my initial reaction had been to dismiss the error as just a mistake on my part. I had surely just misread the instructions and that was that. But now that I knew my wife had independently made the same mistake. There had to be a reason we’d both made the error.

I suspected the font. Were the ‘7’ and the ‘1’ easily confused? Looking again at the instructions, they aren’t easily mistaken at all. Perhaps this was poor lighting, reading at the wrong angle, or my eyesight was finally going.

But as I read these instructions over and over again, something dawned on me. The measurements are laid out in tabular form, but if I were to read it out loud, it would go something like this.

Number of level scoops per feed (1 scoop = 4.8g) Quantity of water per feed ml Approx. 1 beaker

7

210

The emphasis is mine. But these key figures are the parts that stand out.

- per feed

- 1 scoop

- per feed

- 1 beaker

- 7

The repetition of words or symbols associated with 1’ is significant. We’re subject to the priming effect and our brains tricked into reading the ‘7’ as a ‘1’. The priming effect is the idea that exposure to something will subsequently influence how we respond to something else. Our brains had been primed to jump to the conclusion that 7 was now 1.

But neither of us could think of other occasions on which we’d made the same mistake. The difference between a 1 and a 7 is usually important and so if anything we tend to pay more attention when reading numbers.

It turns out, that when we are exhausted, tired or depleted, we are more susceptible to the priming effect.

Quote from Thinking, Fast and Slow, p81

If there is one thing that is sure about early stage parenting, it’s that “tired and depleted” are a considerable understatement.

Conclusion

As a parent, one of the things I’ve tried to focus on is reassuring our eldest that it is OK to make mistakes. We all make mistakes and whilst it may not feel nice to admit when we do, you can be sure that we all do it. But I’ve never stopped to consider why we make mistakes. Yes, we might be tired, we might not be checking our work, we may just be thinking about something else.

But when two of us made the same mistake in quick succession, I started to wonder. Is there a reason this happened? Can we explain what happened? And, whilst I can’t be certain, the idea of the priming effect coupled with near permanent exhaustion feels like a plausible explanation.